A reflection on growing up unseen in fantasy literature, and the joy of writing my own worlds where queerness is front and center.

Long before I had the vocabulary or lived experience to understand what it meant to be gay, I knew I was different. It was evident to me that my inner world didn’t match that of my peers, that I was harboring my own kinds of sensitivities, anxieties, passions, and preferences—whether they were considered acceptable or appropriate by the world around me or not.

As a child, I found other boys to be simple and mysterious all at once. I felt more at ease with girls. They wanted to listen to music, pursue creative endeavors, and engage in imaginative play. Meanwhile, the boys in my age bracket seemed to only care about playing and watching sports.

I felt lost, somewhere in between two worlds. I knew I could never live up to the heavy expectations society had placed on me even at an early age. I needed somewhere to belong, somewhere I could be who I was inside.

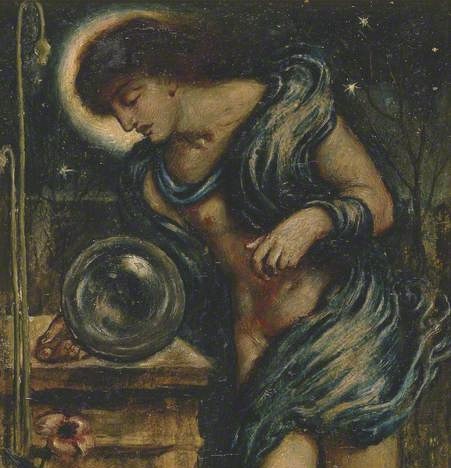

Like so many before me who felt at odds with others, I found an escape in books. I transported myself to fantasy worlds where magic overcame fear.

I can still picture myself in my room at my parents’ house, curled up in bed with a well-worn hardcover, poring over the pages of The Hobbit or The Crystal Cave. I wished more than anything that I could live in Middle-earth or Arthurian England. Later, when I discovered the Harry Potter series, I convinced myself my invitation to Hogwarts was lost in the mail. I devoured anything I could read in the fantasy genre, spanning from Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea to Neil Gaiman’s Stardust. And before I could even read, children’s fantasy films like The Last Unicorn, FernGully, and The Sword in the Stone were in regular rotation on my TV.

It’s safe to say I’ve been a lifelong fantasy nerd. It’s been an escape for me for as long as I can remember. But for most of that time, it was a genre that kept true belonging for a kid like me just out of reach. I loved the stories without seeing someone like myself in them. I never got to experience seeing a fully realized gay protagonist who wasn’t either ornamental to the story or subjected to tragedy because of their identity.

Even if I didn’t realize it at the time, I was searching for gay characters on every page.

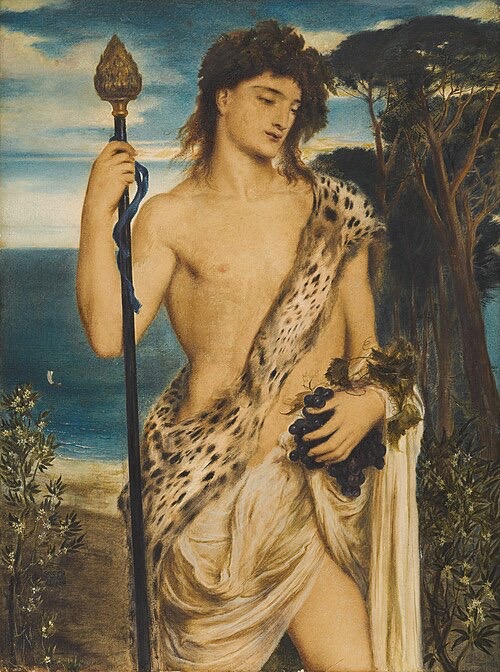

When I first encountered Merlin in Mary Stewart’s trilogy retelling the Arthurian saga from the famous wizard’s perspective, I did not know to call him queer-coded, but that is certainly how I felt. Merlin was deep and introspective, detached from society, and harbored inner magic that set him apart. Most of all, his interior life was devoted entirely to another man. His unending loyalty to King Arthur seemed beyond friendship.

I recognized something similar in Frodo and Sam’s relationship when I read The Lord of the Rings. I’m under no illusions that Tolkien wrote them as queer characters. I know he was tapping into the homosocial bonds he’d experienced with real-life soldiers on the battlefields of World War I. Nevertheless, the bond between those two hobbits resisted easy labeling; it portrayed a kind of love and tenderness I’d rarely seen between men.

I was desperate for real representation—and Frodo and Sam were much better than what I’d been offered before. From Dracula to vain, lisping Disney villains, media couldn’t resist portraying queer-coded characters as the ones we weren’t supposed to trust, the ones who’d foil our heroes.

But even then, we were expected to read between the lines. Queerness was implied, especially for antagonists. But we still weren’t on the page.

Fantasy didn’t invent those patterns of exclusion. It inherited them from a broader culture shaped by religious fear, censorship, and the lingering ghosts of the Hays Code. It may have seemed to me that the genre I was obsessed with was on a mission to permanently exclude me, but moral panic and discrimination existed in society first. These ideas simply bled through to our stories and then permeated our media for generations.

As I got a bit older, my frustration with not seeing myself in the worlds I loved grew. By the time J.K. Rowling tried to toss us some crumbs by retroactively casting Dumbledore as a gay man, people like me had taken matters into our own hands, writing and reading fan fiction stories that paired characters denied romance on the page, like Harry Potter and his best friend Ron Weasley, or even his sworn enemy Draco Malfoy. Fan fiction gave young writers, including me, a space to practice telling our stories on our own terms, to write ourselves into the books we cherished.

In recent years, fantasy has taken tentative steps toward representation, lighting brief sparks that seemed to extinguish before they could burn too brightly. I felt a sense of pride when Renly Baratheon was treated with relative dignity on the HBO adaptation of Game of Thrones, only to see his storyline, his love, and his life painfully cut short. The lesson seemed to be that queer love was possible in the genre, but definitely not survivable.

For a lot of us LGBTQ+ fans, GoT was far from our first taste of tragedy for our favorite gay characters. Many fantasy readers encountered a gay protagonist for the first time reading Magic’s Pawn by Mercedes Lackey, published in 1989. Vanyel’s sympathetic portrayal was an ambitious undertaking and truly groundbreaking for its time. Vanyel seemed to be exactly what I’d been searching for all those years growing up: a gay character who was fully human—sensitive, powerful, capable of love.

But Vanyel’s story was saturated with sorrow. His sexuality was a burden, an albatross around his neck. His queerness was interwoven with tragedy. That book meant the world to me, but it left me wanting more. It made me want to tell my own stories, and to write them from my perspective. Because what I needed more than anything was a vision of a world where being gay didn’t hurt. That same world I wanted to read in every book.

These days, I require more than imperfect representation. I’ve been longing for queer characters written by queer authors. Luckily, there is an explosion of this very thing in fantasy right now. Writers like TJ Klune, Tamsyn Muir, and Shelley Parker-Chan are penetrating the mainstream and topping the bestseller charts at Barnes & Noble and Amazon—it’s something that my younger self never imagined would become the reality. There’s a growing movement for me to join now, a chorus of queer voices reshaping a genre to fit those of us who always wanted to belong in it.

I’ve wanted to be a writer for as long as I could remember, but it was only within the past few years that I started to consider the possibility that I could write the stories I really wanted to tell, the books I wanted to read.

When I began creating Ulstra, I knew I wanted to build a society that had never learned to fear queerness. I wanted to write a world where sexuality was another part of life—not a basis for discrimination, violence, or hatred. Ulstra still has conflicts driven by power and politics. But they don’t run parallel with our world’s homophobia, racism, and sexism.

I have no patience for people who find a world like Ulstra unrealistic. If we can imagine dragons, elves, and sorcerers in our fantasy settings, we can envision enlightened societies where homosexuality isn’t punished.

Writing in this world has been a liberating experience. I now realize that this is my utopia—not the worlds I grew up reading, but the one I wrote where someone like me can be the main character of the story.

Ulstra has become the world I once searched for, the world I’d wished Camelot or the Shire could have provided for me as a young reader.

In Crystals of Ulstra, my first book that I hope to publish next year, I’ve imagined a gay male protagonist—a mage and forest guardian named Koralo whose story revolves around purpose and love rather than shame and secrecy. His closest companion, Delfen, is straight. He’s brawny, but gentle. Their friendship mirrors my own experience of camaraderie between gay and straight men: affectionate, loyal, and uncomplicated.

Roko, a bisexual soldier, grows into self-understanding gradually, discovering that desire can be wider than the categories he inherited. Lazuro, the prince and antagonist, is gay, but his ambition, not his orientation, defines his downfall. Gerda, a crystal seeker, identifies as agender in a culture that accepts difference with curiosity rather than disdain. Cejana, a lesbian mage, is ambitious, witty, and entirely herself. Identities exist without prejudice; none of them exist to prove a point.

Ulstra also reimagines how gender norms work. At the mountain fortress Zirkono Minado, military service is considered a feminine pursuit and the arts are the province of men. Tondra, brave captain of the Gardistona, commands her troops with strength and compassion while courting a painter-turned-politician. The inversion isn’t satirical, but a reflection of the variety of people I’ve known in real life. Straight or gay, masculine or feminine, no one I know fits the rigid boxes that fiction used to impose. I wanted to write a world that felt closer to that kind of lived complexity.

Despite the strides we’re making in fantasy, today’s real-world political climate carries echoes of the one I grew up in. When LGBTQ+ people are cast aside or vilified, it’s incumbent upon us to continue telling our stories proudly and undeterred. I want to do that—and I’m called to do it.

Writing a queer fantasy trilogy feels like coming home. I write queer fantasy because it’s what I was meant to do all along: write the books I always wanted to read. Rather than looking for myself in others’ stories, I’d write them myself. And in turn, I hope that I am providing a world that can be an escape for others like me, too, a place they can find themselves in fantasy. Now that I’ve started down this path, I never want to stop.

Follow along on social media as I write my queer fantasy trilogy:

Bluesky | Mastodon | Threads | Instagram

Read more writing updates on Crystals of Ulstra from my blog:

People of Ulstra Series: Meet Gerda

Introducing Gerda Etagemo, Crystal Seeker of Zirkono Minado.

Esperanto: The Language of Ulstra

How a constructed language found a home in my “hopepunk” fantasy world.

People of Ulstra Series: Meet Rubena

Introducing Rubena Rugastono, Mago of Taumaturgio.

Leave a reply to Five writing goals for 2026 – Bradley Bowen Books Cancel reply